Every single day millions of cigarette butts end up in nature – they get thrown on the ground, on pavements, in to storm drains, even directly in the sea. Cigarette butts are the most common litter item in the world. Globally 4,5 billion cigarette butts end up in nature every single year. This means millions of butts every single day.

Cigarette butts are made of cellulose acetate and contain several toxins, such as cadmium, lead and arsenic, and in water they break down to microplastics and release toxins in the surrounding waters. When a cigarette butt enters a water environment it starts leaking these substances within hours. Research has shown that the consequences of these toxins in water bodies are deadly for the fish and other marine life (Proctor, 2011).

Cigarette butts are not biodegradable

Despite of the common belief, cigarette butts are not biodegradable but pose a serious environmental hazard. When in water, if exposed to sunlight, cigarette butts break down to tiny pieces, never entirely disappearing but becoming diluted in water. Microplastics then again have the ability to soak in additional chemicals from the water environment surrounding them. This means these microplastic particles can become tiny transporters of hazardous chemical substances into our food chain.

Every year thousands of cigarette butts are collected during beach clean-ups, but this is only the tip of the ice berg. Globally, it has been estimated that 40% of litter found on beaches is smoking related. Along the Baltic Sea, cigarette butts are by far the most common litter item, making up to 67% of all litter items found on beaches. The average number cigarette butts found on urban beaches in the Central Baltic area is above 300 butts/100m (MARLIN-project). Considering that only 15% of all marine litter ends up on beaches, this means the number of butts in the water is much higher.

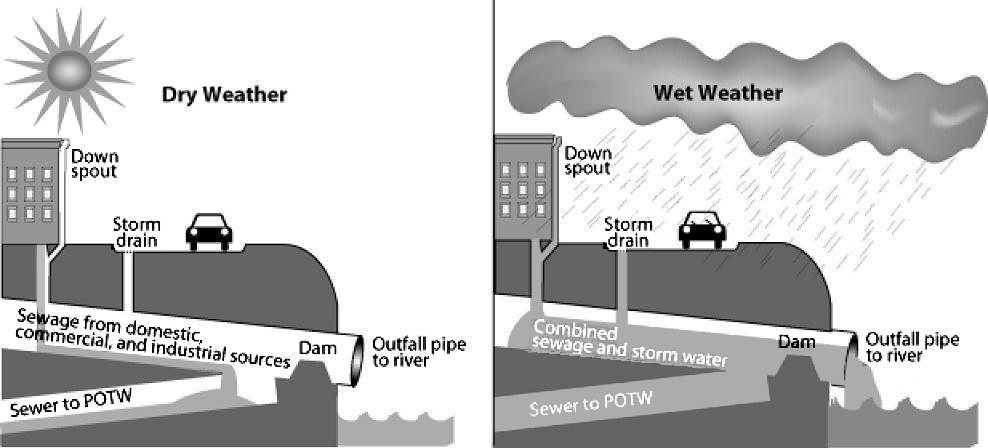

Storm drains are not waste bins

80% of all marine litter comes from land-based sources. A cigarette butt does not need to be thrown directly into water to end up in the sea – it can travel a long way. A significant amount of marine litter comes from the urban environment: trash that is thrown on the street gets flushed down into storm water drain systems that takes it directly to a water body nearby.

“Before reaching the drain, rainwater collects and carries garbage, salt, pesticides, fertilizers, animal waste, oil and fat, soil and other potential impurities. Contaminated rainwater damages lakes, rivers, wetlands and the sea” Says Pilar Meseguer, project coordinator for iWater, Interreg funded project for integrated storm water management.

Storm water is water from rain or melting snow that does not soak into the ground. It can travel long distances in built environments – from roofs through coated surfaces such as paved streets, parking lots and sidewalks, to the street wells. Storm waters are mainly discharged through separate sewage drainage networks. As an example, the city of Turku (Finland), one of project BLASTICs pilot areas, has a storm water drain network of over 550km. These drains lead the water flows from rain and melting snow directly into water bodies nearby.

“In Europe it is common that cities also have mixed sewage drains. Turku has more than 50km of mixed sewage drain system that takes storm water and sewage to a treatment plant, but in times of heavy rain, the waters also end up in the sea.” – Pilar Meseguer

In times of heavy rain or large amounts of melting snow, the storm water drains are under a lot of pressure and get easily overflooded. This is a known issue and it is expected to become an even bigger issue in the coming years due to climate change increasing rainfall.

Sources:

- Marlin final report

- https://suomenash.fi/faktaa-tupakasta/tupakka-uhka-ymparistolle/

- Portland State University Health Department (2013): Fact Sheet: Environmental Impact of Tobacco

- Proctor, RN. (2011) : Golden holocaust: Origins of the cigarette catastrophe and the case for abolition,

- Los Angeles and Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, page 492

- https://www.integratedstormwater.eu/about